The mountain of time. Exploration of a Palaeolithic camp in La Garma

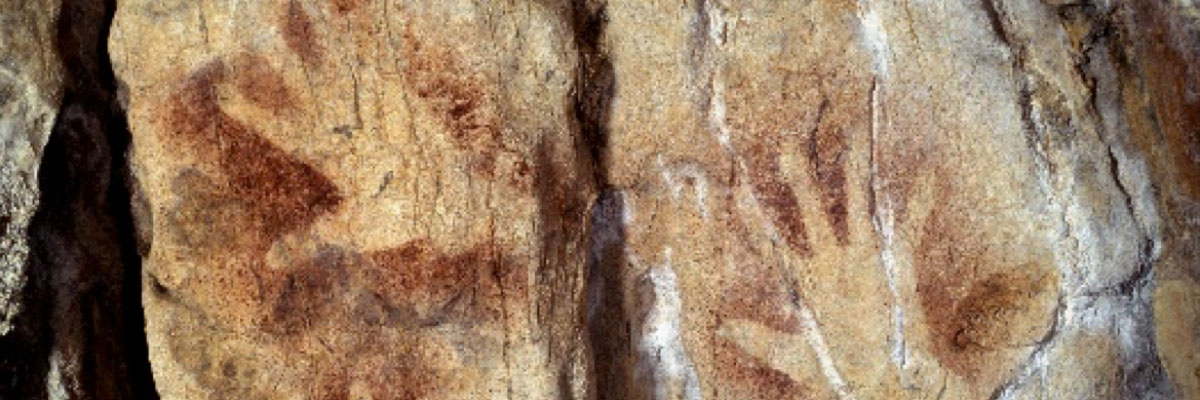

With the discovery in 1995 of the archaeological complex of La Garma, the Lower Gallery, a unique site in the world, together with one of the widest and most complete cultural sequences in Europe, was discovered. It also includes a large collection of cave art, which has deserved to be included in the UNESCO World Heritage List, and one of the most relevant collections of mobile art in the world. But what is really exceptional about La Garma is that it allows us to enter a terrain normally off-limits to archaeological research: the extraordinary conservation of soils and structures from the Upper Palaeolithic in the Lower Gallery offers unprecedented possibilities for the study of the dwellings and ritual spaces of the hunters of the last ice age.

Period

The Garma houses one of the most complete sequences of world prehistory, with testimonies from all periods, from the Lower Palaeolithic to the Iron Age, and even from the Middle Ages. However, the Middle Magdalenian occupations (16,500 years), a unique set of occupation lands and constructions in the world, stand out.

Institution

International Institute of Prehistoric Research of Cantabria (IIIPC) (Universidad de Cantabria-Government of Cantabria-Santander)

Web and social networks

https://scope.unican.es/proyecto-la-garma/

Principal Investigator(s)

Pablo Arias Cabal

International Institute of Prehistoric Research of Cantabria (IIIPC), Universidad de Cantabria.

Roberto Ontañón Peredo

International Institute of Prehistoric Research of Cantabria (IIIPC), Museum of Prehistory and Archaeology of Cantabria (MUPAC) and Prehistoric Caves of Cantabria, Government of Cantabria.

Location

Cueva de la Garma, Cantabria

LOCATION

RESULTS

The most outstanding result of the project is obviously the initial finding and documentation of the Magdalenian soils of the Lower Gallery, one of the great discoveries of the Paleolithic in the second half of the 20th century.

The identification of nine Magdalenian huts (figs. 2 and 3), something unusual in a subway environment. They were built from a base of stones and stalagmite blocks that held a structure of light materials (sticks and skins) that was also fixed to the ceiling of the cave. Recently it has been demonstrated that one of them (IV-B) included a lion’s skin of the caves.

It is also very relevant to note that, in addition to a camp, there were areas dedicated to the ritual. This is the case of Zones III and IV, located inside the karst, without natural lighting, where small cabins were built in places with very low ceilings.

The cataloguing of the rock art includes more than 500 graphic units. Patterns of distribution have been observed that contradict the traditional hypothesis of a separation between cave art and habitat sites, since the existence of paintings and engravings in the camp area has been

confirmed.

We have identified a Palaeolithic path that leads to a room with paintings.

For its mobile

art alone, La Garma would already be an exceptional site in the European Palaeolithic concert. To date, 14 objects made of horn or bone and 46 platelets with engravings have been documented, to which we must add the existence of precise data on their origin and manufacture.

Also noteworthy is the location in La Garma A of the oldest signs of human presence in the Cantabrian region, with an age of nearly 400,000 years.

The works in La Garma are also a milestone in the field of Paleontology. The discovery of a complete skeleton of a cave lion (Panthera spelaea), dated in 10685 BC, the most recent specimen known in the world, is still unpublished.

Also very relevant is the Mesolithic burial of El Truchiro (5900 B.C.), whose study has confirmed that the corpse (a young woman) had been deposited on an oak bark, a practice of which only one analogous case is known in the entire European continent.

PICTURES

- Archaeologists Discover Port Structures from Ancient Greek City of Asine (Ancient origins 11/03/2025) - 12 March, 2025

- LiDAR study reveals 5,000-year-old fortified settlements (Heritage daily 11/03/2025) - 12 March, 2025

- Unlocking the Secrets of Jersey’s Le Câtillon II: A Celtic Settlement Discovered Near the Enigmatic Hoard (Arkeonews 12/03/2025) - 12 March, 2025